After a decade working for Hollywood executives in Los Angeles, Emily Pennington decided to change her life and spend it outdoors as much as possible. She bought a temperamental minivan she named Gizmo to live in, and set out on a yearlong road trip to visit all sixty-three national parks, hoping to make it through the adventure in one piece. On the road, she found herself navigating a painful romantic breakup and non-stop obstacles—from the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic to wildfires and hurricanes—that threatened the trip, her safety, and her peace of mind.

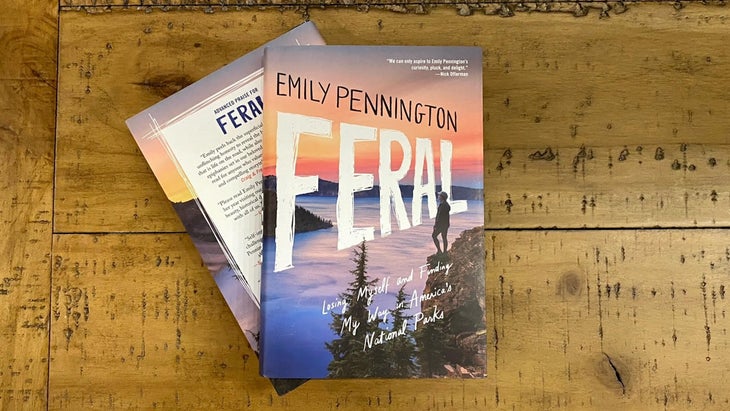

En route, she wrote about each national park in Outside‘s 63 Parks Traveler column. And now she’s published a compelling book about the experience called Feral: Losing Myself and Finding My Way in America’s National Parks. Below is an excerpt of one our favorite chapters on how she found the strength to hit the road.

I drove toward Yosemite with the shattered pieces of my life, empowered by the thought that I could now build them back into whatever shape I wanted. When I reached the valley floor, I was surrounded on all sides by enormous walls of granite. El Capitan and Half Dome stood like friendly, stone-bound greeters saying hello to all who passed through, and the warm hues of autumn were ever present. After I pulled into my campsite at Upper Pines, my legs were itching for a walk, so I took off down the nearest trail to Mirror Lake. I let my feet carry me past gray squirrels and immense pines, all the way to a sandy pit where the lake should have been, had California not been in a historic drought. The vertical wall of Half Dome’s western face blushed in the late sun.

Mosquitoes began their invisible, Doppler-like buzzing around my head, but rather than turn back to make dinner, I felt compelled to climb to the top of a nearby boulder and lie flat on my back to watch the light shift across the famous granite dome.

David was an Eagle Scout with the body of a lumberjack and the heart of a poet. It was his fault that I had grown obsessively fond of backpacking in the five years leading up to my quest to visit every park. I fell madly in love with his ability to quote Epictetus over penne arrabbiata and his infectious adventurous streak; years before we met, he and a group of friends had plotted a six-month course from Los Angeles to Rio de Janeiro. By bicycle. Riding past an onslaught of fish-taco stands, dodging dengue fever in the thick jungle, and surviving a police shakedown, his posse had managed to do the unthinkable—prove that ordinary people with nine-to-five day jobs can save up, set off on a professional-adventurer caliber trip, and survive relatively unscathed.

Not having come from an outdoorsy family, my first-ever backpacking trip was in Sequoia National Park at the ripe age of twenty-eight, under David’s watch. I was a complete junk show. Donning a backpack left by Airbnb guests at my former apartment, I hunched, apelike, under its weight as my lungs quickly learned (and hated) what the air feels like above nine thousand feet. Among the assorted sundries inside my pack was a bohemian leather jacket, a full-sized towel, and a child-sized sleeping bag, covered in a purple paisley print with peace signs, from the sale bin at a suburban H&M.

David wasn’t aware that this was my first backpacking excursion. And I didn’t know that he didn’t know. So when he suggested a twelve-mile journey up to the summit of 11,207-foot Alta Peak and bedding down in the high-altitude meadow that shares its name, my youthful bravado and desire to impress him lit up, and I said yes. I did yoga three times a week—what could go wrong?

What I didn’t know was that, once you reach a certain elevation, the air becomes noticeably thinner and thinner, until walking uphill requires a tremendous amount of effort and concentration. I felt like I was sucking air through a wet paper straw as we ascended in the afternoon sun. Without a chest strap, my backpack clung to my shoulders like a limp orangutan and swung frustratingly to and fro whenever I moved. By the time we made it to camp, I was a girl crumbled.

My stomach growled ferociously from the exertion, and David carefully assembled his little aluminum backpacking stove and delicately screwed its hose onto a fuel canister. Click. Click. Click. The lighter failed to ignite the gas inside the metal burner. This left us with two options: soak our dehydrated backpacking meal in cold water, making a crunchy and unsavory soup of bland calories, or use chocolate to bribe the hikers at the next campsite into letting us borrow their stove.

Not fifteen minutes later, we had arranged our makeshift rock chairs into a circle of former strangers and were passing around a Nalgene filled with scotch whiskey that made my head spin beneath the dazzling brightness of the Milky Way. A woman pulled a ukulele out of her pack, Mary Poppins style, and the six of us howled at the moon as we belted out the lyrics to familiar pop songs.

The next morning, after a fitful night spent tossing and turning in our cramped one-person tent, I awoke to find the meadow and the High Sierra beyond it awash in pink-hued light. It was my first sunrise in the Great Western Divide, and though I had spent most of my adult life up to that point in a strictly secular mindset, something about the soft glow and the stillness of the morning hushed me into reverence.

What impractical magic had I stumbled upon? A forest-laden Burning Man for athletic hobbits? A blister-bearing mountain temple for misfits?

A lot of people have a rare and poetic transformation in the woods. They find god or something like it and emerge reborn. I suppose the experience might be akin to one’s first experience with psychedelics—the world appears one way your entire life and then, suddenly, it isn’t.

What happened to me was somewhere between a god moment and a boot camp. I saw the light, sure, but I couldn’t walk straight for three days. I was blistered and bruised. I was ravaged and raw. I was hooked.

It was oddly fitting, then, that my relationship with David collapsed inside a national park. The wild likes to wring out all unnecessary claptrap and excess baggage until you’re left naked and exalted and clinging to the truth.

“It’s not me, it’s you,” I found myself saying one Saturday evening in Yosemite, before my parks journey was even the seed of an idea. A full moon beamed auspiciously overhead like a spotlight as we assembled a small fire beneath the granite eye of Half Dome. “I’ve done everything I can to impress you. I took up rock climbing. I’m a competent outdoorswoman now. I organized a threesome. Hell, I’m even faster on trail than you are these days. Why won’t you just call me your girlfriend?”

David stammered into speech before the thought had fully formed.

“Because . . . I . . . I don’t think we would make very good domestic partners.”

“Oh.”

I began trembling in great sobs, fearing my organs might melt out through my skin as I wept. My chest rattled as I struggled to take in air. My worst fears were coming true. My efforts went unnoticed. My best would never be good enough. My adventurousness and impulsivity were charming for about a year, until it was time for him to get serious—with someone else. I felt like the worst version of the manic pixie dream girl trope: the manic outdoorsy dream gremlin that everyone wanted to sleep with but no one wanted to take home to mom.

In that moment, I needed to know that someone could love me unconditionally, absent of achievement, and maybe it was a fool’s errand all along. But I’d been chasing down that elusive partner ever since. And now, in the final months of my parks journey, I was realizing that the only person that someone could be was me.

After things with David fell apart, it took a long time to build myself back into something resembling the woman I wanted to be. I lolled around at my desk job for months. I slept with dozens of strangers. I stopped eating. I started force-feeding myself meal replacement drinks.

But as my heartsick intensified, so, too, did my love of the wilderness. I took a class to learn how to use an ice axe and crampons and started setting my sights on higher peaks and bigger adventures. Rather than elevate another man to godlike status in my mind, I began going out every weekend and throwing myself against the ragged canvas of the mountains. And though my new lifestyle felt raucous and healing, I needed more.

One day, on a hiking trip through Kings Canyon with a girlfriend, the thought hit me with all the ferocity of a locomotive barreling toward my chest: What if I was less in love with David and more in love with the adventures he introduced me to? What if I struck out on my own and planned a yearlong journey across America, solo? Across the one thing that had stirred me awake, ripped me wide open, and stitched me back together again—the national parks.

I didn’t need a partner in crime to set off on a grand adventure. I had two perfectly good feet, a dirt-caked backpack, and a fire inside my heart.

Now, back in Yosemite four years after that fateful trip with David, I felt it all come back to me. I was staring up at the exact spot where we had ended things. Past melded with present, and I found myself experiencing a wallop of déjà vu, simultaneously feeling the weight of two shockingly similar realities–I’d severed ties with my most recent partner, Adam, on a hiking trip too, in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. What is it with me and breakups in the fucking national parks? I wondered. Maybe it was something about how truth reigned supreme in the wilderness. It was all trees and rocks and elements of the ancient. The ultimate stress test for any relationship. The wild could be counted on to rip out anything that wasn’t real or worthy from my life.

As the sunset turned fire red on its slow descent, I realized something else: that my moment of deep loss with David under those smooth stone slabs cradled this one. It was that singular night that catapulted me into exploring the parks and becoming so proficient in the outdoors that I would never again need a man to guide me. It stood to reason that this moment of sorrow might also be cradling some incredible, unforeseen future that I couldn’t yet fathom. I had come so far in four years. Where would I be in four more?

To escape the heat and the wildfire haze, I spent much of the next morning driving up to the park’s high-altitude Tuolumne Meadows area, making a pilgrimage to Elizabeth Lake before the afternoon crowds arrived. A perfect reflection of Unicorn Peak lay suspended in the glassy water while insects occasionally skittered across its slick surface. I wandered around the lake, the only person on the trail, and clambered onto a large boulder facing the humpbacked mountain. It was the same spot where, almost two years earlier to the day, Adam had suggested that we perform a relationship commitment ceremony, writing vows and declaring our love.

From my backpack, I removed a small Ganesha statue, a stick of palo santo, a lighter, and a list of vows I had written. I fingered the late-season grass, crisp and nearly golden, and snapped off two identical strands from the ground below. After carefully tying them into a circular shape on my left ring finger, I lit up the fragrant wood and started reading my script. If I couldn’t find a partner, I would marry myself.

I promise to be gentle with myself and let whatever emotions arise come and go calmly and with great care.

I promise to love myself unconditionally. I promise to love my thoughts, even the less charming ones.

I promise to stand by myself in sickness and in health.

I choose patience, trusting that the work I am doing is true and meaningful and that I don’t need to beat myself up to have amazing things happen.

With tears streaming down my face, I kissed the feet of my little bronze Ganesha, remover of obstacles, patron saint of new beginnings. A woodpecker began her percussive search for breakfast. I gazed up and laughed. The morning sun warmed my face.

With my heartache distilled into a few blades of grass wrapped tightly around my finger, there was nothing to do but move forward. Flinging myself across the country toward Cuyahoga National Park in the wake of so much emotion seemed a prime situation for drama, but I mostly spent my days listlessly flipping through Johnny Cash and Rilo Kiley playlists. I belted out the lyrics I knew as I passed high, pine-scented mountains near Flagstaff, countless Route 66 travel stops, and the painted flattop mesas of central Arizona. I pulled over to sleep at a Love’s truck stop, the incessant hissing of 18-wheeler breaks and deranged railroad horns making the scene feel more like a three-ring circus than a legal place to sleep for the night. At 6:00 a.m., I finally rose when a car alarm failed to stop screeching after twenty minutes.

The road was mostly dull, with the occasional rust-hued plateau, field of cows, or gust of hot wind. I texted a friend to see if he had any recommendations near Amarillo. Just keep driving, he replied.

I had never seen fall colors out east before. For years, I had known about their heart-stopping magic from movies and television shows, but the all-American rite of passage of actually seeing them in person had never graced my life until I reached Cuyahoga Valley, my forty-eighth national park.

Tucked between Cleveland and Akron, the park was more urban than most, its sprawling woodlands home to various historic buildings and railroad stops. With a thin ripple of clouds blanketing the horizon, I pulled into the parking lot for one of the area’s most beloved hikes—Brandywine Gorge—and began meandering along its mile-and-a-half loop. Steep rock walls lined with mosses and hanging gardens soon loomed overhead as I neared the area’s main attraction—Brandywine Falls. A swift cascade of water trickled over terraced ledges of stone, looking more like a series of lace ruffles on a debutante’s gown than the roaring torrents of rivers pouring over the edges of cliffs in Yosemite Valley. I walked on. A canopy of canary-yellow maple rustled above me, and I lifted my gaze skyward, trying not to trip over tree roots. This is real autumn, I thought as I hiked along slowly, watching the wind turn leaves of rust and marigold into tiny paper airplanes that wafted gently onto the forest floor. It was as if the trees were throwing a giant party, exploding into one final burst of elaborate color before embarking on their cycle of hibernation and rebirth.

When the sun began its nightly descent toward the horizon, I hightailed my van over to Ledges Overlook, a series of rough sedimentary rocks that fall away steeply to a bird’s-eye view of the park’s glorious foliage. From the perch I could see for miles. Lit up in late evening sunlight, the warm rainbow of fall colors looked even more magical, and as the clouds turned a brilliant shade of tangerine, two dozen other hikers sauntered out of the woods and stood stock-still, taking it all in. When the last of the sun faded, we scattered and went our separate ways, the spell broken. I felt more at peace than I had in a long while.

I awoke wrapped in my sheets as a wash of pastel morning light made its way across the farmlands outside Akron. With rain in the forecast, I needed to hustle if I wanted to explore more of the park. After a breakfast of oatmeal and instant coffee, I spun my wheels toward Century Cycles, rented a bike, and started down the Towpath Trail. It instantly found a place on my list of the best urban riding paths.

The trail was intermittently paved and gravel, paralleling the Cuyahoga River and the ruins of locks that once served as a portage for ships carrying goods from Lake Erie down to the Ohio River. Now long abandoned, historic canals sprung up here and there beneath apricot-hued leaves that seemed to burst forth from every tree. I zoomed past old wooden storefronts and miles of fiery fall colors, thinking about my future as I raced the rain.

I would like a vintage, courtyard-style apartment. I would like a medium-sized dog. I would like to go skiing with my mother and find a devilishly handsome man to press my warm body against, but preferably not at the same time.

It felt healthy—excavating a way forward from the vantage point of a swiftly moving vehicle. Like carving a new path allowed me to enjoy the trip more. If I was chained to travel because there was no other option, travel would lose all novelty and wonder. There had to be hope. There had to be a future to look forward to.

Emily Pennington, a freelance writer based in Los Angeles, visited 60 national parks in 2020. Just before this article went to press, she explored American Samoa, her 63rd and final park.

How to Get Reservations at These Popular National Parks in 2023

The post In Her New Book “Feral,” The Author Recounts Visiting Every U.S. National Park in a Year appeared first on Outside Online.